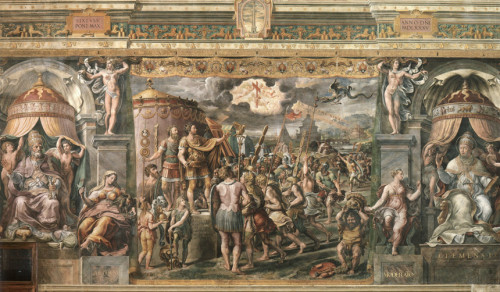

However, before we answer this question, let us go back to the start of the year 1520. The works in the papal apartments (Raphael’s stanzas) are progressing at full steam. Raphael, accompanied by his students and a throng of aides had just finished the frescoes in the Stanza dell’Incendio di Borgo and is preparing the cartons needed to decorate the next room – this time a much larger one, which was to be used for representative purposes. It is here that official meetings between the pope and important guests are to take place, and ambassadors from all over Europe are to be present. Pope Leo X, calmly looks on as the works are being completed. The new room 10 x 15 meters was to be adorned by large-format paintings (imitating, in accordance with the newest fashion) tapestries hanging on a wall. Raphael is already preparing the necessary sketches and plans, and even, despite the fact that he is burdened with various other jobs, has personally begun to paint some of the figures, experimenting with a new technique. This time, he desired to replace frescoes with oil painting, hoping that he would be able to achieve the subtlety of a drawing, the sweetness of color, and the delicate sfumato – so often praised in his canvas paintings. The sudden death of the young artist on the 6th of April 1520 was a blow not only for the whole artistic community, his enthusiasts, and clients but also for Pope Leo X, who sincerely mourned his trusted painter. The barely begun works in the new room awaited continuation but they lacked coordination. Ultimately the pope entrusted them to Raphael's students, among whom the greatest talent was exhibited by Giulio Romano, Giovanni Francesco Penni, Raffaellino del Colle, but also others, who had many a time proven their skill in the previously completed papal chambers. However, not feeling comfortable with the oil technique, they returned – under the tutelage of Giulio Romano – to the tried and tested fresco technique. We are not completely sure how much they changed the cartons of Raphael and if he was indeed able to prepare all of them, especially since two designs had to be prepared from the beginning. Initially besides The Vision of Constantine and The Battle of the Milvian Bridge two more scenes were to be completed: The Presentation of the Prisoners to Constantine and Emperor Constantine Refuses to Bathe in the Blood of Innocents. Why did the next pope, Clement VII change his mind and ordered the preparation of two different scenes? Generally, it is assumed that he wanted to be immortalized in them but also to set out a very current and important for him political program. And thus, the works were completed in 1524. The main wall which was also the largest shows the great battle scene in which Constantine defeats his adversary Maxentius during the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. On the left, we will witness the scene preceding the battle, on the right – the scene of the emperor's baptism by Pope Sylvester. If we turn towards the window, we will further notice The Donation of Constantine, meaning the act of giving the city of Rome to Pope Sylvester. And it is those two scenes – the most controversial as far as historical facts – which were ordered to be painted by Clement VII.

Let us analyze the frescoes in chronological order, to recognize the idea of the popes and the artists who created them.

The Vision of the Cross is the scene taking place prior to the famous battle, which had forever changed the fate of the world. The weaker army of Constantine is preparing for the battle against the forces of Maxentius. The emperor notices a cross in the sky and hears the voice "In this sign, you will conquer”, which we can see on the fresco in the Greek version, ἐν τούτῳ νίκα. We find out about this vision from Eusebius of Caesarea – a Christian chronicler who describes this event in his famous work Vita Constantini. According to another chronicler, Lactantius, on the night preceding the battle, Christ appeared to Constantine in a dream. Taking this to be a sign Constantine ordered his soldiers to decorate their shields with the Christogram XP, which ultimately led to their victory. On the fresco, Constantine, as is customary for leaders, is speaking to his soldiers prior to the battle, standing on a marble pedestal adorned with the inscription: ADLOCUTIO QUA DIVINITATIS IMPULSI CONSTANTINIANI VICTORIAM REPERERE. In the background, we can see a bridge connecting the two banks of the Tiber (perhaps the Sant’Angelo Bridge) but we will also see other elements: the Meta Romuli Pyramid, in the past found next to the Circus of Nero, Hadrian's Mausoleum, and the Mausoleum of Augustus, ancient obelisks, columns and statues of ancient Rome – a city that was thoroughly pagan, but which would from that moment change its face, becoming the heart of the Christian world.

The following, main scene adorning the room is The Battle of the Milvian Bridge – the heroic and monumental vision of the victory of Constantine over the drowning in the Tiber Maxentius. The victor is accompanied by three angels, pointing in three different directions – in the direction of the defeated Maxentius, symbolizing the fall of paganism, in the direction of heaven, thanks to which Constantine was able to complete the deed, and finally in the direction of Rome – the future apostolic city.

The next scene – The Baptism of Constantine – is proof of the emperor’s gratitude for the victory and aid of the Christian God, but also a sign of subjugating himself to God’s will. Pope Sylvester – Christ’s vicar and the successor of St. Peter, thus accepts Constantine into the Christian commune. This all takes place in a building reminiscent of the San Giovanni in Laterano Baptistery while happening in the company of clerics and other Christians ready to accept the sacrament of baptism. On both sides, we can also see some strange guests, who seemingly bear witness to this act. Among the figures, we can recognize the king of France Francis I (on the left) and Charles V, the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire – two political adversaries of Clement VII (who commissioned the painting), and whose features can be seen in the face of Sylvester. As we can imagine, the humble, semi-nude (defenseless) Emperor Constantine is to be an example for them, of how a Christian ruler should behave. From the book held by the pope, we can make out a sentence: Hodie salus Urbi et Imperio facta est (Today is the salvation of the city and the empire). Here the pope decides to support a lie – Constantine was baptized not by the Bishop of Rome Sylvester, but by Eusebius of Nicomedia, anointing the emperor on his deathbed in that very city.

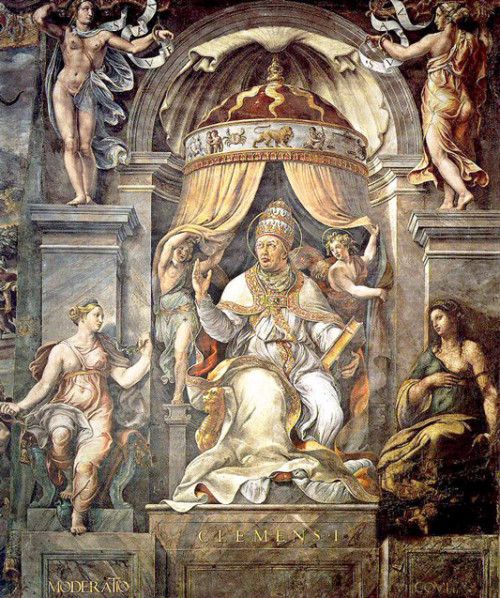

And finally the last scene – The Donation of Constantine. In a beautiful, column interior of the old Constantine Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano, Pope Sylvester, is seated on a podium, as he receives a golden figurine symbolizing Rome (Dea Roma) from the hands of Constantine, who is kneeling before him. With this gesture, the emperor gives the city and the whole of the Western Empire to the pope. The pontiff accompanied by his dignitaries and representatives of the secular world, surrounded by the people, blesses the emperor, whose head is adorned with not the imperial diadem but with a laurel wreath. The fresco relates to a document knowns as the Donation of Constantine, which even when the painting was being created, was already subject to heavy criticism. In 1440, the humanist Lorenzo Valla recognized it as a falsification. The Church, however, for centuries maintained that it was legitimate and only admitted to the hoax in the XIX century. However, using a document that was already at that time seen as discredited is difficult to comprehend. Why did Pope Clement VII, whose features also appear in the face of Sylvester on this fresco, subjects himself to criticism? Confronted with the widespread of the Reformation, humiliated by Catholic rulers, Francis I and Charles V, he reminds them of the obligation to subjugate themselves to the papacy, due to tradition and law, but most of all due to the primacy of the Roman Catholic Church, stemming all the way from Constantine. Thus the decoration of the walls in the Hall of Constantine fits perfectly with the plan of the papacy wanting to recall the first Christian emperor with a specific goal in mind. The frescoes were to depict the victory of Christianity over paganism, in relation to which Constantine was simply a tool in the hands of God. Pope Clement VII, seems to suggest that he is the continuator and the successor to a plethora of saint popes, including Saint Peter, who deserve respect; some of them can be seen among the paintings.

From the left we can see:

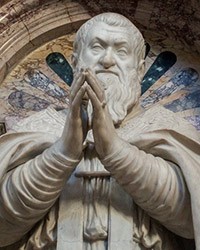

- Saint Peter – between the personification of the Church and Eternity, and Pope Clement I, between Gentleness and Kindness (The Vision of the Cross)

- Pope Alexander I – between the personifications of Faith and Religion and Pope Urban I between Justice and Charity (The Battle of the Milvian Bridge)

- Pope Damasus between the personifications of Peace and Innocence and Pope Leo the Great between Innocence and Purity (The Baptism of Constantine)

- Pope Gregory the Great and Pope Sylvester I (The Donation of Constantine)

Two of these personifications – Justice (Iustizia) and Kindness (Comitas) – are of particular significance to us, since they were painted by Raphael. During a five-year-long renovation which was finally completed in 2020, the former glory was restored to the Hall of Constantine. The frescoes were cleaned uncovering hidden details of the paintings, and the authorship of the two allegories painted in the oil technique was finally confirmed.

But that is not all, what the hall has to offer. In a plinth that surrounds it with illusionistic paintings imitating both marble bas-reliefs as well as bronze reliefs, we will notice scenes from the life of Constantine intertwined with the life of Saint Sylvester.

Directing our gaze upwards, we will notice a wealth of allegories, putti, and cartouches with the pope's insignia and coat of arms. The original, wooden ceiling, finishing off the entire Hall of Constantine – was in 1582 replaced by a vault and decorated with frescoes. In it, we can easily see winged dragons – the element of the coat of arms of the pope who commissioned these works, Gregory XIII, as well as a griffin covered by a sash – the coat of arms of the next pope, Sixtus V. The central painting of the vault represents the Triumph of the Christian Religion and its victory over the pagan idols (Tommaso Laureti).

Interestingly enough, at the time of struggles between Catholics and Protestants, it was the latter, who accused the former of idolatry.